Your cart is currently empty!

Williams Brown

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Dolor, alias aspernatur quam voluptates sint, dolore doloribus voluptas labore temporibus earum eveniet, reiciendis.

Latest Posts

Categories

Archive

Tags

Social Links

Plastic waste is recognized as a major cause of environmental harm, with products like water bottles, plastic bags and clothing fibers acknowledged as major contributors to plastic pollution—but research by University of Toronto environmental scientists shows another source deserves more attention: paint.

In a study published in the journal Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry, researchers in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s department of ecology and evolutionary biology show how paint has been severely understudied when it comes to research on microplastics.

Defined as plastic particles less than five millimeters in size, microplastics are known to accumulate in air, water, food and even our bodies over time—and have been shown to have toxic effects on both marine life and human health.

The researchers say paint has been severely underestimated as a microplastic pollutant because it can be difficult to identify.

“Often, paint will show up as ‘anthropogenic unknowns’ when characterizing microplastics,” says Zoie Diana, post-doctoral researcher who co-authored the study with Assistant Professor Chelsea Rochman and master’s student Yuying Chen. “Researchers have been wondering what such particles are and hypothesizing, based on computer modeling, that paint might be responsible for a large portion of them.”

To investigate this further, the researchers surveyed existing literature to determine where paint pollution comes from. They found there were around 800 studies published on microplastics in 2019, but only 53 focused on paint, making for a significant research gap.

Although paint has traditionally been considered a form of plastic, on average, 37% of it is composed of synthetic resins that bind pigments together.

To help fill the gap in the research, Diana is creating a spectral library—a technique to identify the molecular structure of unknown fragments.

She notes that there are many measures being employed to reduce microplastic pollution—for example, rain gardens, landscape sites which absorb polluted stormwater.

“Rain gardens installed by major highways in San Francisco have been shown to reduce downstream microplastic emissions by 91 percent, which is a really high success rate,” she says. “You can also install a filter in your washing machine that will capture microfibers before they’re passed along to the wastewater treatment plant.”

Where paint is concerned, some existing measures include special vacuums that can prevent paint emissions from leeching into the environment during building construction.

Diana says it’s vital to devise and deploy more measures to reduce paint pollution, given the ubiquitous nature of paint.

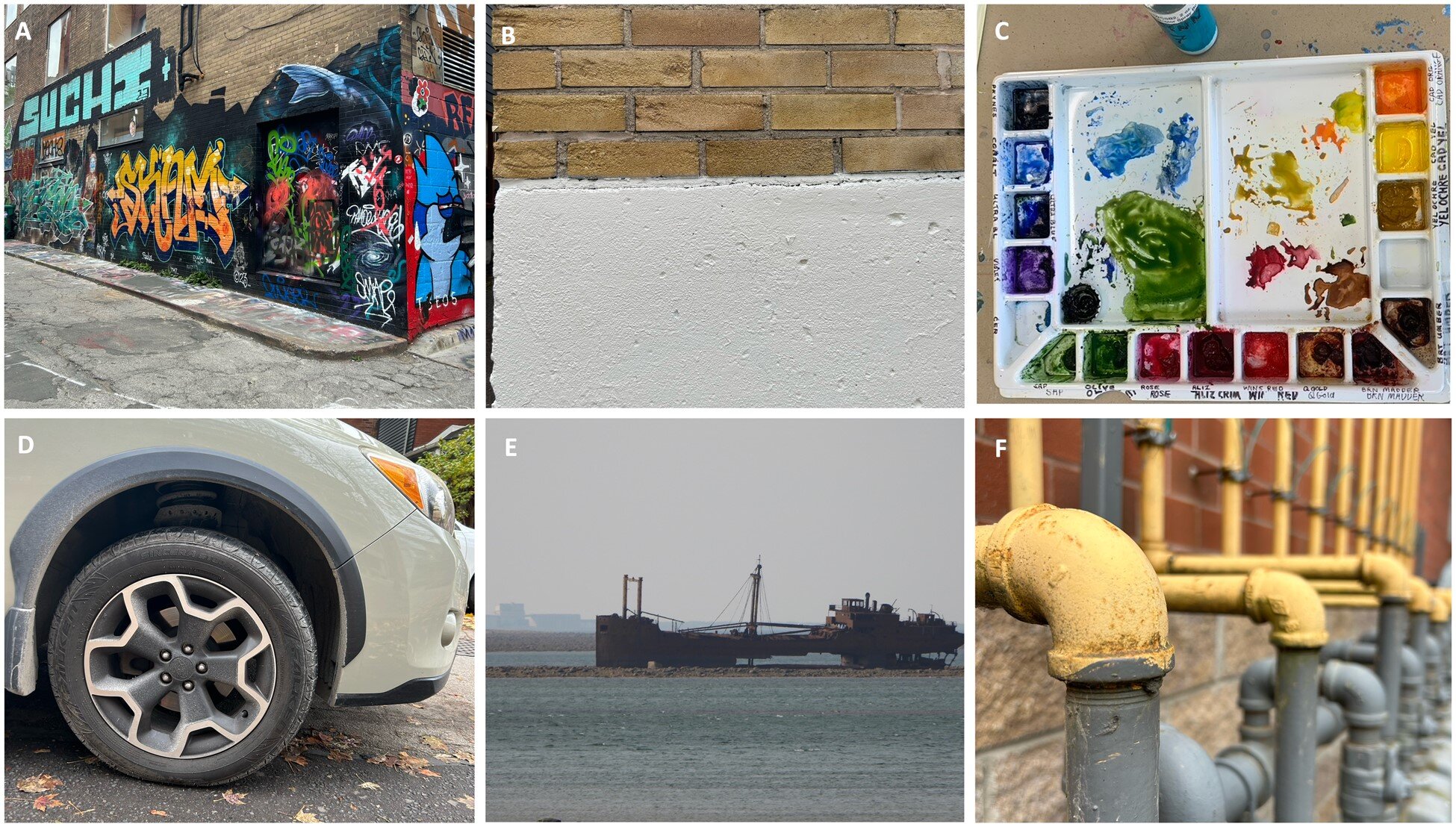

“There’s paint from boats. There’s also paint on buildings, on our roads. Once you walk around the city, you start to see it everywhere you look,” she says.

She’s also optimistic that a global plastics treaty will be signed in the near future. “That’s something that’s in the works, and I’m excited to see where it lands—particularly to reduce microplastics, which—as we’ve seen—are found everywhere.”

More information:

Zoie T Diana et al, Paint: a ubiquitous yet disregarded piece of the microplastics puzzle, Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry (2025). DOI: 10.1093/etojnl/vgae034

Provided by

University of Toronto

Citation:

Environmental scientists highlight role of paint in microplastic pollution (2025, March 4)

retrieved 4 March 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-03-environmental-scientists-highlight-role-microplastic.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.